The Measure of Greatness

by William Pierce

Originally from https://counter-currents.com/2011/04/the-measure-of-greatness/

2,525 words

2,525 words

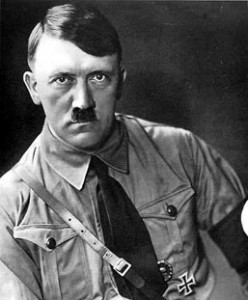

April 20 of this year [1989] is the 100th anniversary of the birth of the greatest man of our era — a man who dared more and achieved more, who set his aim higher and climbed higher, who felt more deeply and stirred the souls of those around him more mightily, who was more closely attuned to the Life Force which permeates our cosmos and gives it meaning and purpose, and did more to serve that Life Force, than any other man of our times.

And yet he is the most reviled and hated man of our times. Only a few tens of thousands of men and women, in scattered groups around the world, will celebrate his birthday with love and reverence on April 20, while all of the scribblers and commentators of the controlled news media, the controlled politicians, and the controlled churchmen will pour out their hatred and venom and lies against him, and those lies will be believed by hundreds of millions.

What is the measure of greatness in a man?

Only the most vulgar and doctrinaire democrat would seriously equate greatness with popularity — although in any polling of average citizens on their choice for the greatest man of the century there are certain to be substantial numbers of votes for Elvis Presley, John Kennedy, Billy Graham, Michael Jackson, and various other high-visibility lightweights: charismatic entertainers on the stage of politics, rock concerts, spectator sports, or what have you.

More serious citizens would pass by the lightweights and choose men who have changed the world in some way. We would hear choices like Franklin Roosevelt (“he saved the world from fascism”), Albert Einstein (“he taught us about the nature of our universe”), and Martin Luther King (“he helped us achieve racial justice”), depending upon whether one’s personal inclinations lay more in the direction of politics, science, or racial self-abasement, respectively.

But if the poll asked instead for the most evil man of the century, or the most hated man, or the man having the most negative influence, at least three-quarters of the blue-collar and the white-collar pollees alike would name one man: Adolf Hitler. This, however, would be merely a reflection of the role assigned to him by the controlled mass media, rather than a truly informed and reasoned choice.

All of this raises several very interesting issues. There is, for example, the question of how we came to the preposterous state of affairs prevailing today, wherein we place the destiny of our nation, our planet, and our race in the hands of a mass of voters whose powers of judgment are manifested in such things as the type of television entertainment their preferences have pushed into prime time and the type of men they have elected to public office. And there is the equally weighty question of how, knowing the ease with which this mass is misled, we permitted virtually all of the media of mass information and entertainment to fall into the hands of a race whose interests are so diametrically opposed to our own.

Perhaps even more pertinent to a consideration of human greatness, however, is the question of how our system of values came to be turned on its head, so that Franklin Roosevelt is regarded as a hero and Adolf Hitler as a villain, not only by the stolid and stunned masses, but also by a majority of the supposedly “educated” elite, many of whom pride themselves on their intellectual independence.

Whether we judge the greatness of a man by his intrinsic qualities of character and soul or by his accomplishments, Adolf Hitler had greatness of a very high order — if we use the standards which have been traditional in our race.

We cannot, of course, make comparisons with all the “mute, inglorious Miltons” whose lack of notable accomplishment has made them anonymous, despite the sterling inner qualities they may have possessed. But when Hitler’s character is held up beside those of other 20th-century political leaders, he stands as a giant among pygmies.

At the prosaic level, we can note his ascetic personal habits, compared with Winston Churchill’s habitual drunkenness and notorious self-indulgence; or his personal loyalty to those who had been his comrades in the days of political struggle, compared with Joseph Stalin’s habit of murdering his former comrades by the dozen, as potential rivals, as soon as he no longer needed their services; or his direct, frank, and straightforward manner, compared to the cunning deviousness which was Franklin Roosevelt’s trademark.

At the spiritual level, the inner differences between Hitler and his contemporaries are even more striking. Hitler was a man with a mission, from the beginning. The testimony of his closest associates, from his boyhood days to the end of his life, agrees with the observations of more distant and impartial observers: Hitler had a mystical sense of destiny, a sense of having been singled out and called by a higher power to devote his life to the service of his race.

His childhood companion August Kubizek has related extraordinary evidence of this when Hitler was only 16 years old (August Kubizek, Adolf Hitler, mein Jugendfreund [Graz, 1953], pp. 127–35). Twenty years later, while he was in prison after an unsuccessful attempt to overthrow the government, Hitler himself wrote of his motivation in a way which suggested the range of his vision:

What we must fight for is the security of the existence and reproduction of our race and our people, the sustenance of our children and the maintenance of the purity of our blood . . . so that our people may mature for the fulfillment of the mission allotted them by the Creator of the universe.

Every thought and every idea, every doctrine and all knowledge, must serve this purpose. And everything must be examined from this point of view and used or rejected according to its utility. Then no theory will stiffen into a dead doctrine, since it is life alone that all things must serve . . .

. . . The National Socialist philosophy finds the importance of mankind in its basic racial elements. In the state it sees on principle a means to an end and construes that end as the preservation of the racial existence of man . . .

And so the National Socialist philosophy of life corresponds to the innermost will of Nature, since it restores that free play of forces which must lead to a continuous mutual higher breeding, until finally the best of humanity, having achieved possession of this earth, will have a free play for activity in domains which will lie partly above it and partly outside it.

We all sense that in the distant future humanity must be faced by problems which only a highest race, become master people and supported by the means and possibilities of an entire globe, will be equipped to overcome . . .

Thus, the highest purpose of a National Socialist state is concern for the preservation of those original racial elements which bestow culture and create the beauty and dignity of a higher mankind. We, as Aryans, can conceive of the state only as the living organism of a nationality which not only assures the preservation of this nationality, but by the development of its spiritual and ideal abilities leads it to the highest freedom . . .

A National Socialist state must begin by raising marriage from the level of a continuous defilement of the race and give it the consecration of an institution which is called upon to produce images of the Lord and not monstrosities halfway between man and ape . . .

It must set race in the center of all life. It must take care to keep it pure. It must declare the child to be the most precious treasure of the people. It must see to it that only the healthy beget children . . .

The National Socialist state must make certain that by a suitable education of youth it will someday obtain a race ripe for the last and greatest decisions on this earth . . .

. . . Anyone who wants to cure this era, which is inwardly sick and rotten, must first summon the courage to make clear the causes of this disease. And this should be the concern of the National Socialist movement: pushing aside all narrowmindedness, to gather and to organize from the ranks of our nation those forces capable of becoming the vanguard fighters for a new philosophy of life . . .

We are not simple enough to believe that it could ever be possible to bring about a perfect era. But this relieves no one of the obligation to combat recognized errors, to overcome weaknesses, and to strive for the ideal. Harsh reality of its own accord will create only too many limitations. For that very reason, however, man must try to serve the ultimate goal, and failures must not deter him, any more than he can abandon a system of justice because mistakes creep into it, or any more than medicine is discarded because there always will be sickness in spite of it.

We National Socialists know that with this conception we stand as revolutionaries in the world of today and are branded as such. But our thoughts and actions must in no way be determined by the approval or disapproval of our time, but by the binding obligation to a truth which we have recognized. (Mein Kampf)

Hitler’s opponents, Churchill and Roosevelt, were party politicians, with the minds and souls of party politicians. Great, impersonal goals, just as truth, meant nothing at all to them. The only thing that counted was the approval or disapproval of their times: the outcome of the next election, a good press claque, votes. Only Stalin shared in any way Hitler’s disdain for approval; only Stalin was motivated to any degree by an impersonal idea. But the idea that Stalin served was the alien, destructive idea of Jewish Marxism. And while Hitler served the Life Force with the instincts of a seer, Stalin served Marxism with the instincts of a bureaucrat and a butcher. A comparison of careers leads us to a similar ranking of greatness of soul. Churchill and Roosevelt were born into the political establishment. They fed at the public trough for years, in one office after another, grabbing greedily at opportunities for a bigger serving of swill. But it was circumstance, not their own efforts, which thrust them onto the stage of world history.

Stalin hacked out his own niche in history to a much greater extent than his western allies, and he was an incomparably stronger man than either of them. He was tough, ruthless, infinitely cunning, and utterly determined to prevail, no matter what the obstacles. Even so, his struggle for prominence and power was entirely within the Bolshevik party and its predecessors. He was the consummate bureaucratic infighter, not the innovator or the lone pioneer.

Only Adolf Hitler started literally from nothing and through the exercise of a superhuman will created the physical basis for the realization of his vision. In 1918, recovering in a veterans’ hospital from a British poison-gas attack, he made the decision to enter politics in order to serve that vision. He was a 29-year-old invalid, with no money, no family, no friends or connections, no university education, and no experience. Liberals, Jews, and communists ruled his country, making him and all those to whom he might appeal for support outsiders.

Five and one-half years later he was sentenced to five years in prison for his political activity, and his enemies thought that was the end of him and his movement. But less than nine years after being sentenced he was Chancellor of Germany, with the strongest and most progressive nation in Europe at his command. He had built the National Socialist movement and led it to victory over the organized opposition of the entire Establishment: conservatives, liberals, communists, Jews, and Christians.

He then transformed Germany, lifting it out of its economic depression (while Americans, under Roosevelt, continued to line up at the soup kitchens), restoring its spirit (and much of the territory which had been taken from it by the victors of the First World War), stimulating its artistic and scientific creativity, and winning the admiration (or, in some cases, the envy and hatred) of other nations. It was an achievement hardly paralleled in the history of the world. Even those who do not understand the real significance of his creation must concede that.

And what was the real significance of Hitler’s work? One of his most earnest admirers in India, Savitri Devi, has given us a poetic answer to that question. She wrote:

In its essence, the National Socialist idea exceeds not only Germany and our times, but the Aryan race and mankind itself and any epoch . . . it ultimately expresses that mysterious and unfailing wisdom according to which Nature lives and creates: the impersonal wisdom of the primeval forest and of the ocean depth and of the spheres in the dark fields of space; and . . . it is Adolf Hitler’s glory not merely to have gone back to that divine wisdom — stigmatizing man’s silly infatuation for “intellect,” his childish pride in “progress,” and his criminal attempt to enslave Nature — but to have made it the basis of a practical regeneration policy of worldwide scope, precisely now, in our overcrowded, overcivilized, and technically overevolved world, at the very end of the dark age” (Savitri Devi, The Lightning and the Sun [National Socialist World No. 1, p. 61]).

More prosaically, Hitler’s work, in contrast to that of his contemporaries, was above politics, above economics, above nationalism. He had mobilized a powerful, modern state and placed it at the service of our race, so that our race might become fit to serve as an agent of the Life Force.

Perceptive and idealistic young men from every nation in Europe — and from many nations outside Europe as well — recognized this significance, and they flocked to serve him and to fight for his cause, even at the cost of censure and ostracism from their more parochial and narrowminded countrymen. There was never before an elite fighting force to match the SS, which by the end of the Second World War had more non-Germans than Germans in it.

The war, of course, is counted as Hitler’s great failure, even as the proof of his lack of greatness, by his detractors. It merely proves that he was a man, not a god, even if a divine will worked through him, and that he could not perform miracles. He could not defend himself forever, with the governments of nearly the whole world allied in a total war to pull him down and destroy his creation, so that they and the interests they served could return to “business as usual.” Even so, he gave a far better account of himself than any of his adversaries.

And what will count in the long run in determining Adolf Hitler’s stature is not whether he lost or won the war, but whether it was he or his adversaries who were on the side of the Life Force, whether it was he or they who served the cause of Truth and human progress. We only have to look around us today to know it was not they.

Post a comment Cancel reply

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

1 comment

Beautiful